When your HVAC system is running, you probably don’t think twice about the ductwork behind your ceilings or walls. But that same ductwork can become a hidden source of water damage, mold growth, and costly repairs—especially when condensation starts to build up. Understanding why ductwork condensates, where it’s most likely to happen, and what can go wrong as a result can save you thousands down the road.

Why Does Ductwork Condensate?

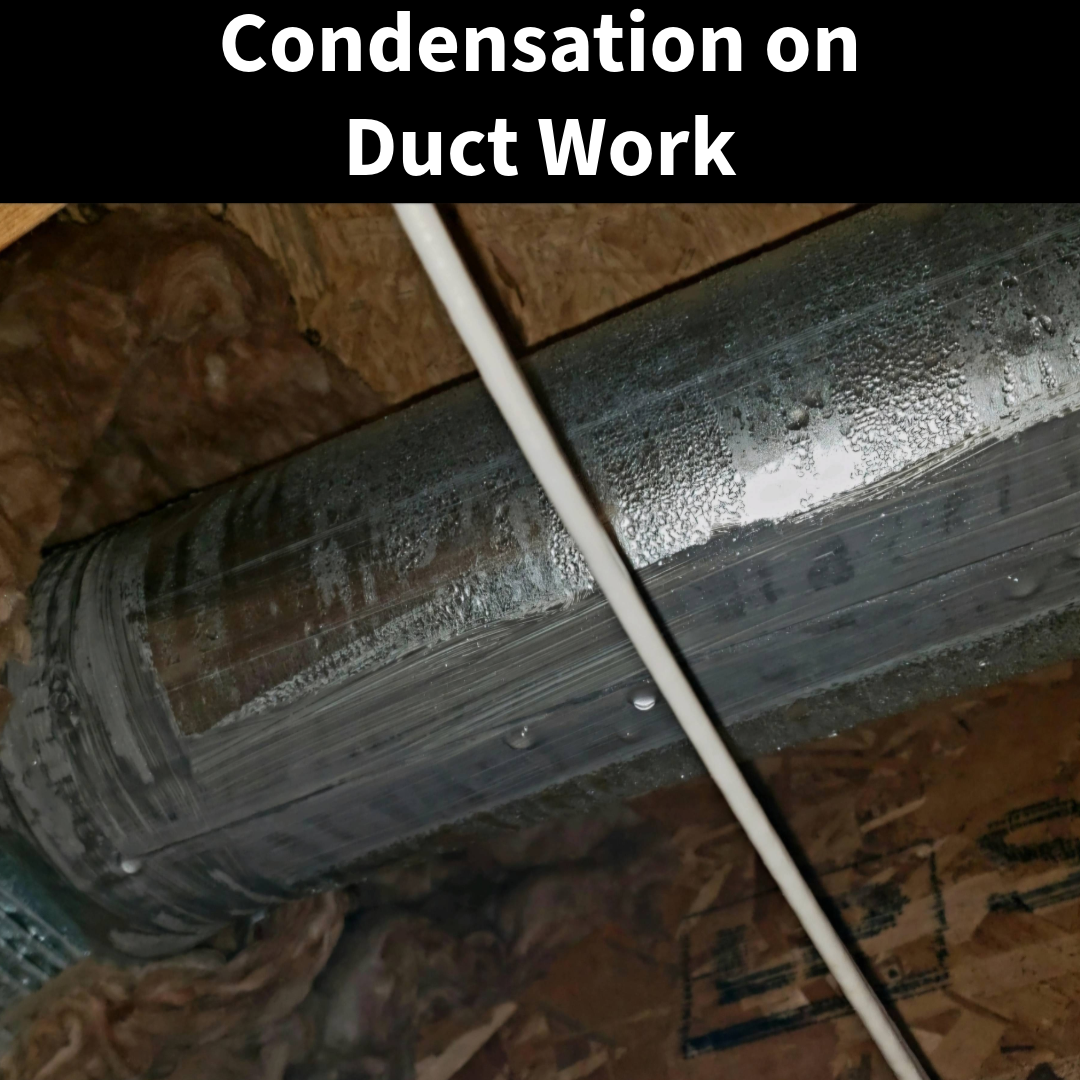

Condensation forms when warm, humid air comes into contact with a cold surface—just like a cold glass of water on a hot day. In your home, that cold surface is often the metal ductwork carrying cool air from your AC system.

Several factors can lead to ductwork sweating:

- High indoor humidity: When indoor humidity climbs above 60%, there’s a greater risk of condensation.

- Poor insulation around the ducts: If the ducts aren’t properly insulated, the cold air inside causes the metal to “sweat” in warm, humid conditions.

- Air leaks: When warm air infiltrates ductwork through gaps, it can trigger internal condensation.

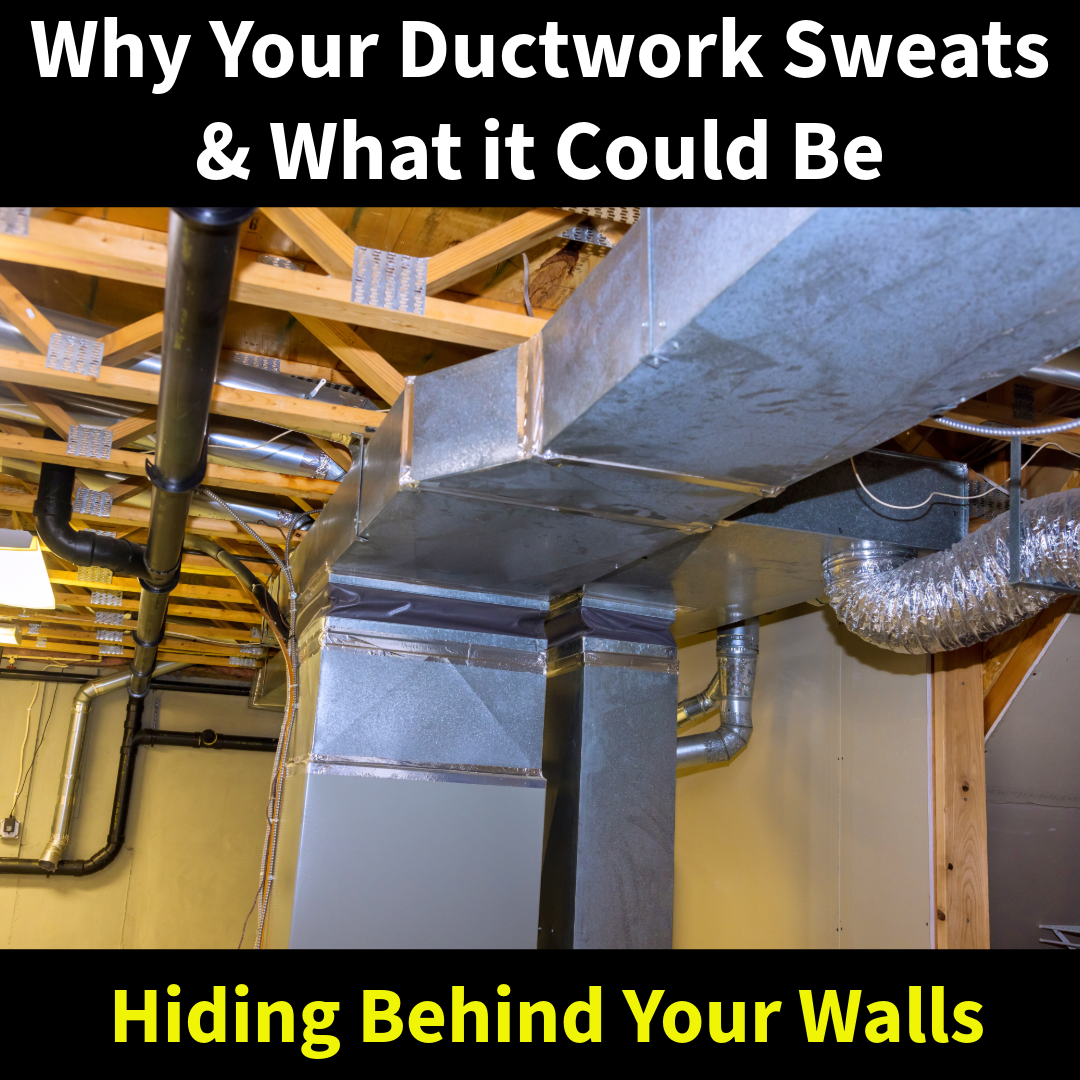

- Unconditioned spaces: Ducts running through areas like attics, crawl spaces, or basements are particularly vulnerable due to temperature differences.

Where It Happens Most

Condensation can occur anywhere ductwork runs, but it’s most common in:

- Basements and crawl spaces – These areas are naturally more humid and often not air-conditioned.

- Unfinished attics – Especially if your home has metal trunk lines running across the attic floor.

- Ceiling spaces – Ducts that run through unconditioned ceiling voids, particularly in older homes, are prime targets.

- Wall cavities – When cool air is pushed through walls that aren’t insulated properly, trapped humidity can result in slow, hidden condensation buildup.

The Damage It Causes

While a little bit of sweating may not seem like a big deal, consistent or excessive condensation can cause:

- Water stains on ceilings or walls

- Rusting or corrosion of ductwork

- Damage to drywall or insulation

- Mold growth in walls, ceilings, or around vents

- Compromised indoor air quality and allergy flare-ups

Over time, that dripping moisture creates an ideal environment for mold colonies to thrive—especially in hidden areas where homeowners may not notice the problem until odors or stains appear.

How to Fix and Prevent It

Addressing condensation issues requires a combination of proper HVAC maintenance, insulation, and moisture control:

- Improve duct insulation

Wrapping your ducts with proper insulation (like closed-cell foam or fiberglass sleeves) reduces surface temperature differences and helps prevent sweating. - Seal air leaks

Use mastic sealant or foil-backed tape to seal duct joints and connections to keep warm air out and conditioned air in. - Control humidity

Use a whole-home dehumidifier or portable units to keep indoor humidity below 50%. Basements and crawl spaces especially benefit from dehumidification. - Encapsulate crawl spaces

Crawl space encapsulation with vapor barriers and dehumidifiers can dramatically reduce ambient moisture and prevent condensation on ductwork. - Check HVAC system performance

An undersized or oversized AC unit can lead to improper cycling and excess moisture in ducts. A licensed HVAC tech can help assess your system. - Routine mold and moisture inspections

If your home has a history of duct sweating, regular inspections can catch early signs of water damage or mold before they become a major problem.

The Mold Risk You Can’t See

If condensation has already caused water to drip behind ceilings or into wall cavities, you may already be dealing with mold growth without knowing it. Musty smells, allergy symptoms, or unexplained stains are all warning signs.

Even small water leaks from ductwork can fuel mold colonies that spread through walls, ceilings, or insulation—impacting both the structure of your home and your health.

When to Call in the Pros

At MSI, we’ve seen it all—from duct condensation slowly rotting out ceiling drywall to hidden mold colonies triggered by a single HVAC leak. Our team offers professional mold testing, moisture mapping, and full-service water damage restoration. We also work with homeowners and HVAC contractors to identify the root cause and prevent it from happening again.

Sweating ductwork might seem like a minor nuisance, but the long-term consequences are anything but small. If your vents drip, your ceilings stain, or you’ve noticed that musty smell coming back again and again, don’t ignore it. Moisture + time = mold. And mold doesn’t go away on its own.

Since 1998, MSI has helped thousands of homeowners throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware detect and resolve hidden moisture and mold problems—safely and thoroughly. If you suspect your ductwork might be doing more than just cooling your air, give us a call.